The main reason I started this blog is because according to the Internet (which, again, does not lie) a successful homesteader is one who can chronicle the work they do and when in something at least loosely resembling an organized fashion. In fact, when I was Google-surfing for Excel templates last morning–don’t give me that side-eye; what else are you going to look up at 3:15 a.m.?–it turns out there are an awful lot of search returns for “garden spreadsheet template”, especially if one opts to throw in the search phrase, “stop judging me.”

Considering I cut my teeth as a drinker on boxed wine, I guess we all know which one of these search returns I immediately bookmarked.

However, it turns out that there is another method to my madness. It turns out that beneath this cool exterior of intellectualism is a really petty, unforgiving kind of person who not only manages to hold a grudge list to rival the likes of Richard Nixon, but also really dislikes things not looking “nice.” My preoccupation with things looking “nice,” admittedly, borders a bit on the pathological; when I was pregnant, I often found myself folding sheets and towels, and then doing it again until I could completely eliminate any visible traces of crease marks.

I also had an unrelenting craving for Taco Bell mild sauce, which is unfortunate because a) heartburn is a major issue for a lot of pregnant women due to acidity imbalances and I was no exception, and b) it’s Taco Bell, which might not seem like a big deal until you stop to consider that I’ve been trying to read 50 books this year and I’m smack-dab in the middle of You’ll Learn to Hate Everything You Put into Your Mouth, by Buzz Killington.

Or, as the literary types prefer to say, Fast Food Nation, by Eric Schlosser.

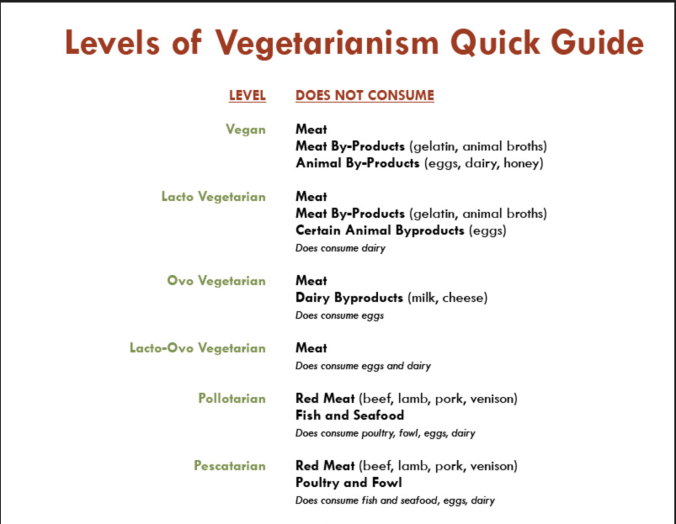

Although Schlosser’s primary target of analysis is McDonald’s, there’s plenty in there to make even the most die-hard fast foodie regret the moment they ever learned to navigate a drive-thru. He doesn’t shy away from exploring the influence and role of food production in creating this “dark side of the all-American meal,” touring slaughterhouses, ranches, and food production factories to literally trace the source of what is served before us. Schlosser might not be the Millennial’s Upton Sinclair, but there’s little doubt that his observations were conveniently timed with the dramatic spike of interest in ethical consumerism, especially as it pertains to lifestyles that attempt to balance nutritional needs with a philosophical commitment to cruelty-free. For many, “cruelty-free” is coded language for the deliberate decision to abstain from eating meat. And it turns out that there is a wide spectrum of what it means to be “vegetarian”:

Seriously, this is a thing. The only thing oddly more unnecessary in its specificity is the determination of what passes for “losing” one’s virginity.

Around the age of nine, I made the decision to convert to vegetarianism–according to this handy-dandy chart, I was firmly in the lacto-ovo vegetarian stage, as I opted to consume byproducts like milk, cheese, and eggs, but refused to eat the actual flesh of the creatures which produced them. At the time, I felt ridiculously self-righteous in my decision to dedicate my diet to my blossoming eating disorder a cruelty-free lifestyle. I was the kind of kid who was obsessed with recycling and saving the Earth, and I liked the idea that nothing would have to die in order to nourish my too-thin paper plate that always came out of the discount bin at Schnuck’s. As a side note, I was also kind of a dick and I liked the idea that converting to a new eating pattern was going to make life more difficult for at least one person responsible for providing me with sustenance (hi Mom).

In actuality, this image is misleading as hell, because the only time I’m ever thinking of my mom is when I’m in therapy, blaming her for my life’s problems, especially my sanctimonious commitment to vegetarianism for more than a decade.

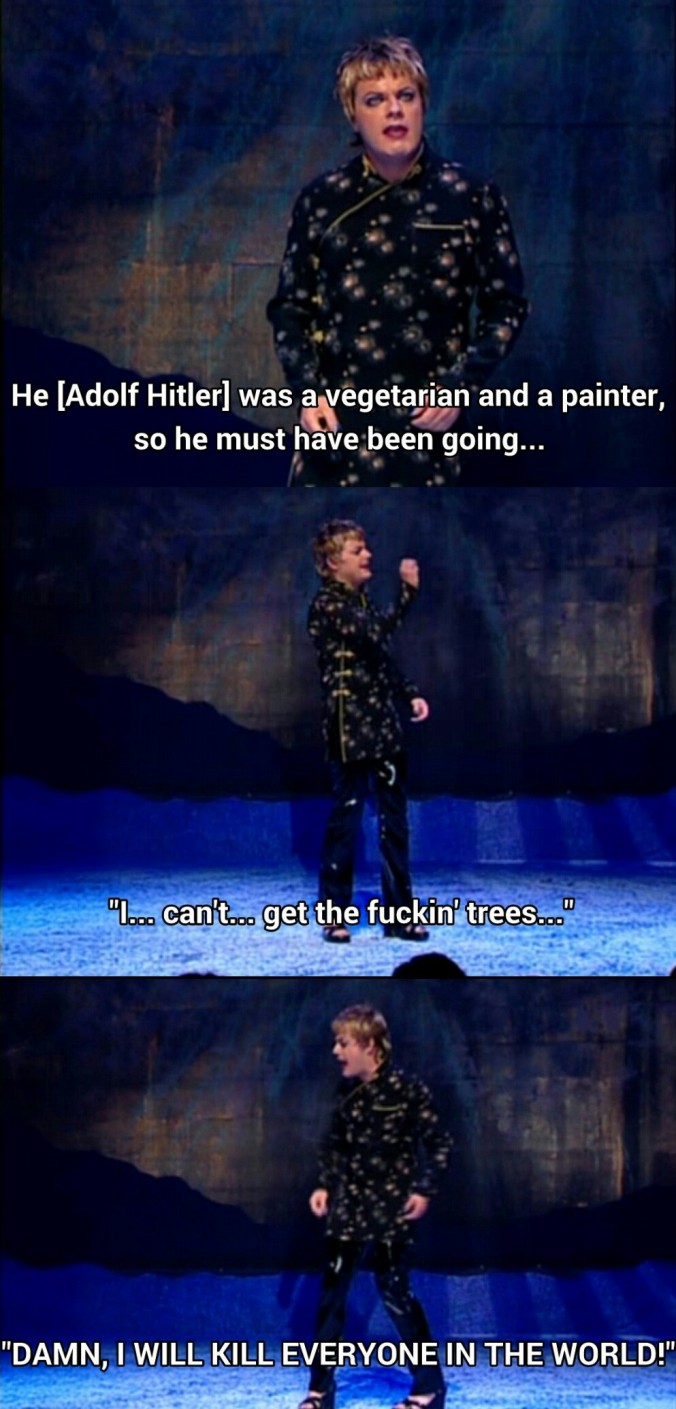

If there’s anything that can be firmly established, it’s that my mom is an invaluable segue into analyzing the dynamics of cruelty, so let’s pretend like I just did a great transition a là the inspired Eddie Izzard‘s particular blend of amazing facial expressions and unique vocalizations and move on. I’ll start by stating the obvious: of course, the philosophy of cruelty-free isn’t without its problems. Amongst other things, it is steeped in both classism and racism, especially when vegetarians get into rhetoric maintaining that animal rights are human rights, and that the two matter equally.

As a pagan, this is a particularly thorny subject of privilege. Unquestionably, racism abounds in all religious circles and faiths, and unfortunately, even Earth-centric spiritualities are not immune from internally promoting it and other forms of oppression. PantheaCon, the largest annual convention for pagan pride in the United States, courted a lot of controversy in 2012 when Z. Budapest, one of the most visible faces of the spirituality umbrella, deliberately and unapologetically excluded transfolx from participating in her otherwise public ritual. However, Budapest is hardly the only manifestation of exclusionary politics under the pagan penumbra; just last year, Humanistic Paganism republished Lupa Greenwolf’s takedown of the Asatru Folk Assembly’s blatant racism, transantagonism, and anti-Semitism.

The piece is worth a read in its entirety, but the most salient observation takes into consideration the accountability factor regarding why a few problematic pagans means the rest of us magickal types must stand up, take note, and work harder.

We pagans have known for decades there were bigots in our ranks, particularly those espousing “folkish” viewpoints–and now there’s absolutely no doubt whatsoever. Not all heathens consider themselves part of the pagan community (and definitely not all of them are racists!), but enough heathens of all sorts come to pagan events and otherwise share in pagan spaces that this declaration by the leadership of one heathen organization is relevant to paganism as a whole.

Greenwolf deserves major props for challenging the community to do better without defensively or regressively recounting the historical baggage that has often accompanied social reception of witchcraft and other Earth-centric systems of belief. As anyone who sat through World Civ or had to read Arthur Miller’s The Crucible knows, merely suspecting another person of engaging in witchcraft was enough to trigger an appearance before a tribunal that ended with the hangman’s noose. The propagation of Catholicism, in particular, did an excellent job of utilizing systems of government to ensure the Christian orthodoxy; arguably the most successful campaign involved the Spanish Inquisition.

To date, this documentary provides the most comprehensive examination of what occurred by the architects of the Spanish Inquisition:

Which nobody was expecting.

Easy Mel Brooks and Monty Python jokes aside, the point is that paganism isn’t without its own baggage of oppression, and that includes internalized expressions of it. In 2015, the pagan community had ruffled feathers over the admitted grave robbing behaviors of a witch named Ender Darling. The 25-year-old resident of New Orleans was accused of removing bones from Holt Cemetery specifically for the purpose of practicing curse work. Darling brought down the fury of the internet when they also attempted to sell leftover bones to other members in the Facebook group, the Queer Witch Collective.

Considering this was long before “But her e-mails” because the penultimate justification for the election of Donald Trump, major props to whoever cleverly designated this event “Boneghazi.” The memes are especially on point.

Political swipes aside, Boneghazi exposed the troubling relationship between witchcraft and white privilege when droves of Wiccans showed up on blogs, denying the existence of curse work within the larger framework of witchcraft. However, the cemetery had been used as a dumping ground for the bodies of indigent people of color, likely the descendants of slaves; in contrast, although Darling identifies as Latinx, they aren’t without white passing privilege. More importantly, the majority of those who came to Darling’s defense were not only white women, but white women who cited the Wiccan Rede as the guiding principle of all witchcraft.

Ignoring the obvious about how there is more than one kind of witchcraft practiced in the United States, many of the guidelines of magical practice within communities primarily made up of people of color have been adapted from nations within the African diaspora that were crushed by the boot of European colonialism. That Darling’s actions came to light as a result of offering bones in a group specifically structured to offer queer witches a digital space removed from the inherent and oppressive structure–specifically, concerning the coded meaning of “black” versus “white” magic–is especially baffling.

As Diana Tournjee observes over at Broadly:

Indeed, what makes the bones discourse so outwardly odd is the way that identity politics and discursive theory are used to code and analyze everything, from living beings to nonliving objects. . .the fact that the group’s moderators appeared to initially be uncritical of Darling represented a violation of the group’s most sacred founding principles. While Darling continued to remind critics that the group had a “no shaming” policy, the argument had no power any longer. Other witches dismissed it, firing back: “There is a difference between shaming and questioning possible ethics and possible oppressive practices—why are we silencing a black witch?”

It is impossible to discuss the Boneghazi debacle without paying close attention to the politics of color. Darling was on the receiving end of the benefit of the doubt due to their white passing privilege, and even those who would otherwise criticize curse work felt comfortable glossing over the point by emphasizing how their own practice of witchcraft meant harming none. And thus, the #notallwitches hashtag was born.

In reinforcing a one-dimensional definition of what witchcraft is, white witches everywhere pushed up on dominant idea as universal, prioritizing one concept of identity over the others despite insisting that “All Lives Matter.” It doesn’t take a trip down the Howard Zinn rabbit hole of authentically taught history to understand that there is a long history of white supremacy deciding, in fact, that human rights don’t extend to every actual homo sapien as it is.

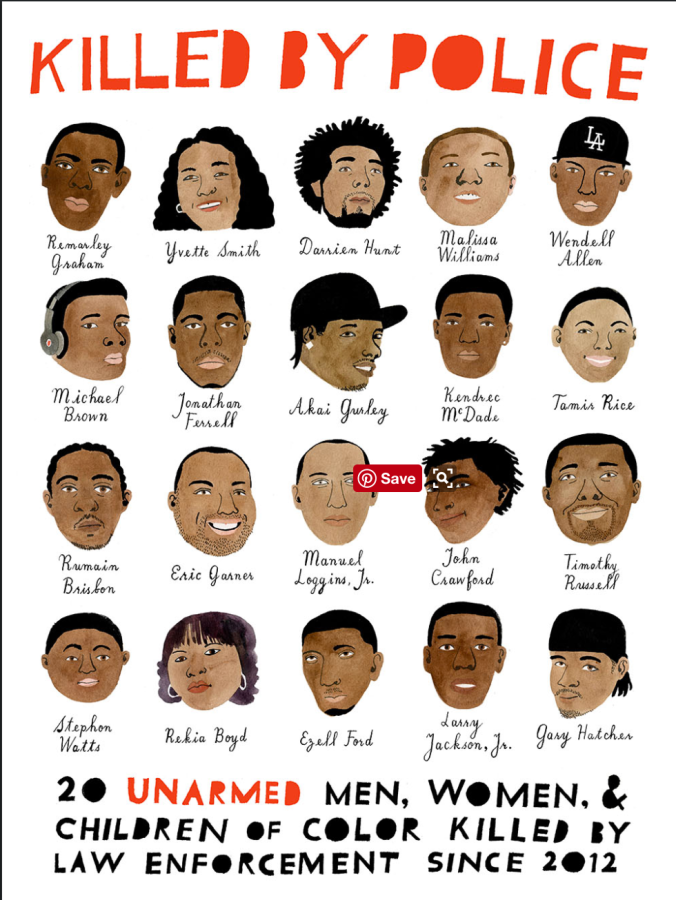

Here are a few people ‘the state’ decided didn’t have an inherent right to life. Brilliant illustration credit to Carson Ellis. Portfolio link: http://carsonfellis.tumblr.com/post/104858108861/some-more-people-to-keep-in-mind-yet-still-only-a

This viewpoint is crystallized over at the blog, Vegan Voices of Color, in a frank takedown entitled “Dismantling White Veganism,” published earlier this year. Veganism, it asserts, has been exclusively whitewashed, and manufactured to create an incredibly one-dimensional presentation of vegetarian lifestyles that not only ignore the lived experiences of oppression still occurring for black and brown people of color, but attempt to equate such historical suffering with renderings of comparable-to-worse fates of animals domesticated for servitude to human beings and wild animals hunted for sustenance and sport. It also reflects why the desire to engage in vegetarianism out of the desire to protect animals is, on the surface, not enough of a challenge to the current way of doing things.

See: Hitler (more on that later).

Anyway, the unnamed author of the piece shares a screenshot of a (presumably, white) vegan arguing that tennis great Serena Williams should be “flattered” by the racist comments that have characterized her as a “gorilla in a skirt.” Another photo features a cow wearing a collar and mouth restraint, positioned next to an artist’s sketch of a stolen black person of color wearing the same implements, and a Helvetica-styled text, suggesting one’s moral barometer on the matter of slavery during the American Civil War is best gauged by one’s current temperament towards animal rights. I’m not sharing either of these photos for the obvious reason that I don’t believe in feeding trolls, and the merit of what I’m getting at is articulated by the author as such:

If the collective goal is to end oppression by evoking a massive awakening in our society, oppression should first be understood—how it functions, how it’s sustained, why it exist. It’s easy to have a one-sided view of oppression when your existence in life is at the furthest location from oppressed. Effectively engaging communities of color in the fight for animal liberation will not be accomplished by telling us to shut up about our issues and focus on animal lives.

Indeed, the way to effectively engage communities of color involves an acknowledgment for how the very existence of slavery continues to promote racism, and discussions on how to address those impacts at their root causes. Not that such discussions are welcome, as Alma Carten observes:

The problem is, no one likes to talk about slavery. For blacks descended from slaves, the subject evokes feelings of shame and embarrassment associated with the degradations of slavery. For whites whose ancestry makes them complicit, there are feelings of guilt about a system that is incongruent with the democratic ideals on which this country was founded.

To be certain, the very discussion of slavery is one of the fastest ways to generate collective eye-rolling from white people, and isn’t something I’m going to shy away from addressing in my blog entries because a) I’m committed to intersectionality, and b) since the majority of people who care what I have to say are already inherently invested in Western frameworks, so the historical significance of slavery cannot be overstated, particularly given the continued propagation of institutional racism that continues to generate disproportionate expectations and outcomes in opportunities across socioeconomic lines, especially as it pertains to education, housing, employment, and health, particularly mental health.

And being in the West also means that vegetarian lifestyles often center the prerogatives of groups like PETA. Which is a problem. A very big problem, in fact; big enough that I’ve written about it extensively. More than once. And, by the way, I’m not the only one; both of my Adios, Barbie pieces are basically drowning in textual evidence from external links about the really fucked elements of PETA. Anyone reading this can certainly mosey on over to drum up some much-needed traffic for my ego, or simply check out Reddit’s pretty succinct summation of why PETA is awful from a few months back.

P.S. Don’t feel bad if you opt for the less-wordy Reddit; my own husband generally avoids reading my articles, unless I do the spiritual equivalent of a “Red Dragon” enactment.

No, actually; he doesn’t.

Of course, I do recognize that PETA and vegetarian lifestyles are not one in the same, much in the same way Jonestown and the cult lifestyle are not one in the same. However, just as Jonestown gave us an endless litany of punchlines regarding the fad of matching track suits and spiked Kool-Aid, PETA provides a seemingly endless supply of behaviors which demand closer inspection and scrutiny. To that end, it is important to understand that vegetarianism is a lifestyle dating back centuries; for many practicing Hindus and Buddhists, vegetarian is a core expression of their beliefs–but more modernly, has been emboldened and propped up by certain food trends; think “superfoods” and “farm-to-table” patterns in advertising and marketing.

And yes, racism abounds in the clever marketing strategies concerning food; it is not a coincidence that many of the so-called “superfoods” like quinoa and asparagus are grown and harvested by poor communities of color, but ultimately possessed by white hands, to be consumed by white mouths, to nourish white bodies. This is a problem, because food has become something more than a way to nurture bodies and provide sustenance; it is merely the latest extension of both identity and respectability politics where the onus is on each person to create gourmet dishes yet not ask from where that food originated, or consider how it is being consumed. We care about what is on the plate, but not how it got there, or what happens once it is cleared.

As it turns out, refusing to wash the dishes constitutes a political act. Please notify the mold growing on Aunt Janice’s casserole pan immediately.

The price goes beyond economic, especially for the countries responsible for exporting these superfoods. Consider the example of quinoa; this hearty grain once served as a staple to the diet of the inhabitants of the Andes, but since quinoa was declared a superfood in 2006, the demand from the United States has driven the price up so that it is no longer affordable to the same indigenous workforce tasked with producing it. According to Blythman, buying chicken in Lima is more affordable than buying quinoa, so many families have no choice but to exist on lower-cost junk food.

In other words, locals are being forced to buy the same kind of food that Westerners are rejecting from their own kitchen pantries in the pursuit of consuming quinoa. We could make a joke about Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 here, but we won’t, because some things are sacred.

Even if they do involve Ethan Hawke.

Talking about the former Mr. Uma Thurman is an excellent transition to not only the process of cooking dead meat (so close) but also evaluating the ethics of eating. The acts connected to eating, from food shopping to actually preparing the food, have come to represent more than just buying and cooking; there is a responsibility to figuring out how to think beyond the plate.

This responsibility to think beyond the plate is one of the motivating factors behind my decision to engage in my own particular brand of half-assed homesteading. First and foremost, growing one’s own food is a radical act, and I don’t mean the kind of radicalism that involves a bomb shelter and 27 hairless cats (though, hey, you do you). I mean the kind of radical act where one is able to offer up some resistance to the system that pits the have-nots against each other from the scraps of the haves. To be certain, even framing the discourse of gardening around possession of the land is entrenched with all kinds of socioeconomic privilege derived from colonialism and settler privilege–the question of whether land should be owned, never mind how such a matter can even be considered, is never asked–but living under the means of capitalism is, currently, inescapable.

More importantly, individualized gardening has long been a means of transgression. In responding to the question of how gardens can serve as agents of radical change, British political science professor George McKay traces the power of gardening through religious, militaristic, and philosophical frameworks to assert, “Notions of utopia, of community, of activism for progressive social change, of peace, of environmentalism, of identity politics, are practically worked through in the garden, in floriculture and through what art historian Paul Gough has called “planting as a form of protest”. Apparently committed to the old-school tradition of presenting both sides in journalism, McKay even discusses the use of gardens in fascist spaces.

Remember how I promised we’d get back to Hitler? Well, now it’s time, because one of the places McKay writes about includes the Polish village of Rajsko, a subcamp made up of flower and vegetable nurseries at the foot of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In other words, scores of women were forced to grow beautiful greenery just miles away from where millions of their relatives, friends, and religious brethren were systematically annihilated.

The Holocaust is a delicate subject to talk about, especially after devoting a dozen or so paragraphs to how gardening and homesteading are ways to subvert colonialism in food production and racism influencing food access. Arguably, suburban gardening has become a matter of life and death for many communities, limited in their options for access to quality food due to the existence of food deserts, areas that are stripped of not only fresh food in the vein of vegetables and fruit, but also noticeably without the convenience of farmers markets or grocery stores.

Awareness of food shortage has increased in the decade since the Great Recession began; Amazon’s recent acquisition of Whole Foods is predicted to have the potential to bridge the gap for hundreds of thousands of food insecure people across the United States, and farms that have the economic staying power of viability are looking at how to bring their produce to the front door of those in need.

These moves, though powerful, are not enough. Real change depends on individuals, ordinary people, confronting the system directly. This is actually the subject of one of my very favorite TED Talks. The presenter, Ron Finley, describes living in South Central, “home of the drive-thru and the drive-bys…the drive-thrus are killing more people than the drive-bys.” Determined to increase access to food within his community, Finley explains how he plants gardens in the geography of urban sprawl and industrialization; his gardens appear in vacant lots, forgotten buildings, and even in the pavement deficiencies of neglected and abandoned roads.

I don’t remember exactly when I first watched Finley, but I do remember being incredibly moved and inspired by his philosophy, branded as guerrilla gardening. Finley chiefly emphasizes what is ultimately on the line for those left to fend for themselves; gardening is not only an act of beauty, it is one of survival and defiance of a system that has no vested interest in keeping people alive. I highly recommend watching the TED Talk in its entirety, as Finley is a natural entertainer and his enthusiasm for his project is contagious, even through the computer screen.

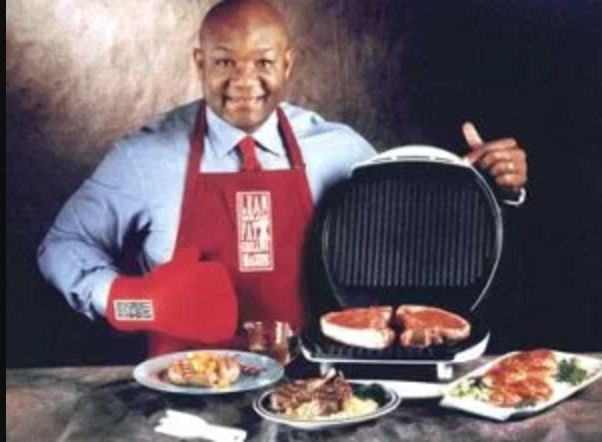

When I began aggressively pursuing the art of self-discovery, one of the allures of paganism seemed–to me–to be a given ability to nurture a green thumb and unleash any amount of charm within a kitchen setting. Connecting with my local Meet-Up group of pagans, I instantly discovered myself within a crowd of people who knew how to make their own bread, properly ferment mead, and work barren ground into an oasis of annual herbs At our very first gathering for feasting, I had to rely on one of them to teach me how to turn on and use my very own George Foreman Grill.

This Millennial’s IQ test.

The point is, while I wouldn’t go so far as to say I pursued witchcraft on the basis that I would receive a buff of superior gardening knowledge when my application to Hogwarts was accepted, I also wouldn’t say that my desire to be more connected with the Earth didn’t enhance my search for a spirituality that would enable me to do exactly that. That is to say, coming into my identity as a homesteader–however much I may be one that is, indeed, half-assing it–constitutes not only a necessary function of allyship, but part of my ever-evolving spiritual journey.

Edit: This is not to say that gardening is easy; far from it. Gardening has been a journey full of a lot of four-letter expletives, comfort food binges, and at least one near emotional breakdown after getting manure in my eye. Pinterest has become my own personal hell as the same women who probably always had perfect handwriting in elementary school have also managed to master growing azaleas in mason jars. I was lucky to have a friend help get me going, but it’s been a lot of trial and error. Google searches aren’t particularly helpful for people with finite resources, but my next entry will attempt to provide more resource gathering along with consciousness-raising.